Over the years, the business model adopted by savings and credit cooperative societies (SACCOs) in Kenya has placed members’ contributions in a precarious position. In 2019, the Ministry of Trade (Currently the overall supervision of SACCOs in Kenya is under the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Cooperatives) conducted an inspection which brought to light the sad state of cooperative societies in Kenya. Notably, Machakos and Mombasa counties were marked as having more collapsed institutions than thriving ones while roughly half of the 1,150 SACCOs registered in Mombasa, Kwale, Tana River, Kilifi and Taita Taveta had closed shop drowning the hopes and dreams of thousands of members. In addition, the Sacco Societies Regulatory Authority (SASRA) suspended several institutions between 2019 and 2020 for breaching regulations and mismanagement of members’ contributions. The institutions that were suspended included Good-Life Sacco, Moi-University Sacco (MUSCO) and Nitunze Sacco. Within the same period, some institutions top management were surcharged for illegal activity and these included, Ekeza Sacco founder, David Ngare and managers of Nyabomite Coffee Society in Kisii County. These and other cases surrounding the operations of saving societies in Kenya captured the attention of the President who gave a directive on the establishment of the Sacco Societies’ Fraud Investigation Unit. Its purpose was to help mitigate fraudulent operations in the division, the subsequent loss of members’ monies and to instill confidence in the sector. The Sacco Societies Regulatory Authority’s chair, John Munuve, formalized this initiative after the Savings and Credit Co-operative Societies (SACCOs) endorsed an agreement together with the Directorate of Criminal Investigation, to pursue this cause.

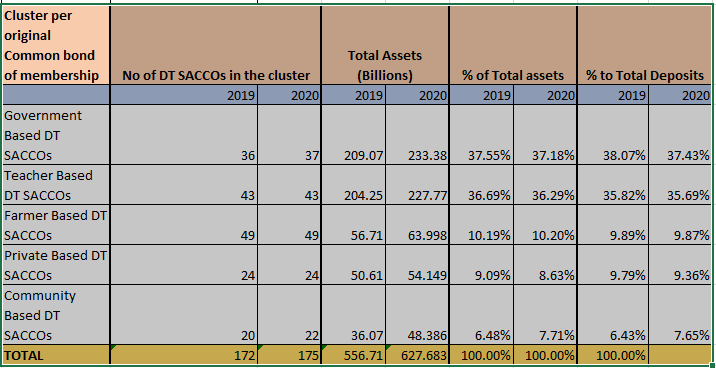

Considering the tremendous growth and potential benefits saving societies have in the Kenyan economy, the President’s intervention through the directive is justified. The table below illustrates the magnitude of wealth held by savings and credit societies between 2019 and 2020. The entire sector had an asset base of KES 617.685 billion and held deposits worth KES 431.46 billion in 2020.

Effectiveness of this:

In October 2019, the Commissioner of Cooperatives, Mr Didacius Ityeng, alluded that the mismanagement of members contribution needed to be addressed and took necessary steps to close down dormant and unsustainable societies. For instance, the case of Ekeza Sacco which saw the founder channel Kes 1.05 billion of contributions to personal ventures (Gakuyo Real Estate) and Eldoret-based Good Life Sacco, whose executive director, Rachael Wachira was charged with siphoning more than Sh1 billion in members’ savings for personal use. According to the Financial Sector Stability Report 2021, the primary reasons for the formation of the fraud unit was to tackle misappropriation of members’ contribution by management, enhance good governance in the sector and instill confidence in members and investors. How then will the investigative unit curb such fraudulency?

To begin with, the sector has entered into a memorandum of understanding with the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission to support in the establishment of industry best practices and instill integrity that has depreciated over the years. This has seen a total of 372 complaints against corrupt officials addressed and measures taken against such misadministration. Following the Memorandum of Understanding, the partnership has remained resilient in enhancing accountability mechanisms in the administration of cooperatives in the country.

Potential collaborations with the Central Bank of Kenya would allow the integration of SACCOs into the national payment infrastructure. This would allow efficient and effective mobilization of members’ savings and real-time reporting of these transactions through the approved clearance of the Nairobi Automated Clearing House. Currently, the participants of the national payment system in Kenya are: the Central Bank of Kenya, the Government, commercial banks, financial institutions and payment system providers. Potentially, deposit-taking Saccos stand to mitigate possible fraudulent risks should they be integrated into the national system.

To prevent further leakages and to tighten oversight measures, cooperative institutions should be required to submit copies of internal audit results and compare these with actual audits at the end of the financial year to the regulating body. For the non-deposit taking entities, they should be strictly regulated to ensure that they do not operate in the manner as their opponents. They should therefore not deal in foreign trade operations or investment ventures.

For effective and efficient performance, the government and other respective regulatory bodies such as the Capital Market Authority (to regulate the liquidity ratios and the minimum core capital levels) should support the Sacco Societies’ Fraud Investigation Unit. Funding from the Government, for instance, can be channeled towards the development or improvement of cyber security systems used. In retrospect, cybercrime was estimated to cost the Kenyan economy roughly 210 million USD in 2017. Moreover, SACCOs have in the past spent an insignificant amount of money towards the advancement of this crucial area. With funding requirements achieved, necessary training and software development could potentially mitigate against infrastructure risks. Parliamentary support through policy legislation, for example review of the National Payment System Act, would accommodate SACCOs in the system. Parliamentary support could also involve the amendment of the Sacco Societies Act to expand the SASRA mandates to include regulation and supervision of non-deposit taking Saccos. Through these fostering initiatives, the idea that SACCOs can be sidelined from national growth and financial inclusion objectives can finally be annihilated.